Credit: NASA, ESA, K. Sahu and J. Anderson (STScI), H. Bond (STScI and Pennsylvania State University), M. Dominik (University of St. Andrews), and Digitized Sky Survey (STScI/AURA/UKSTU/AAO)

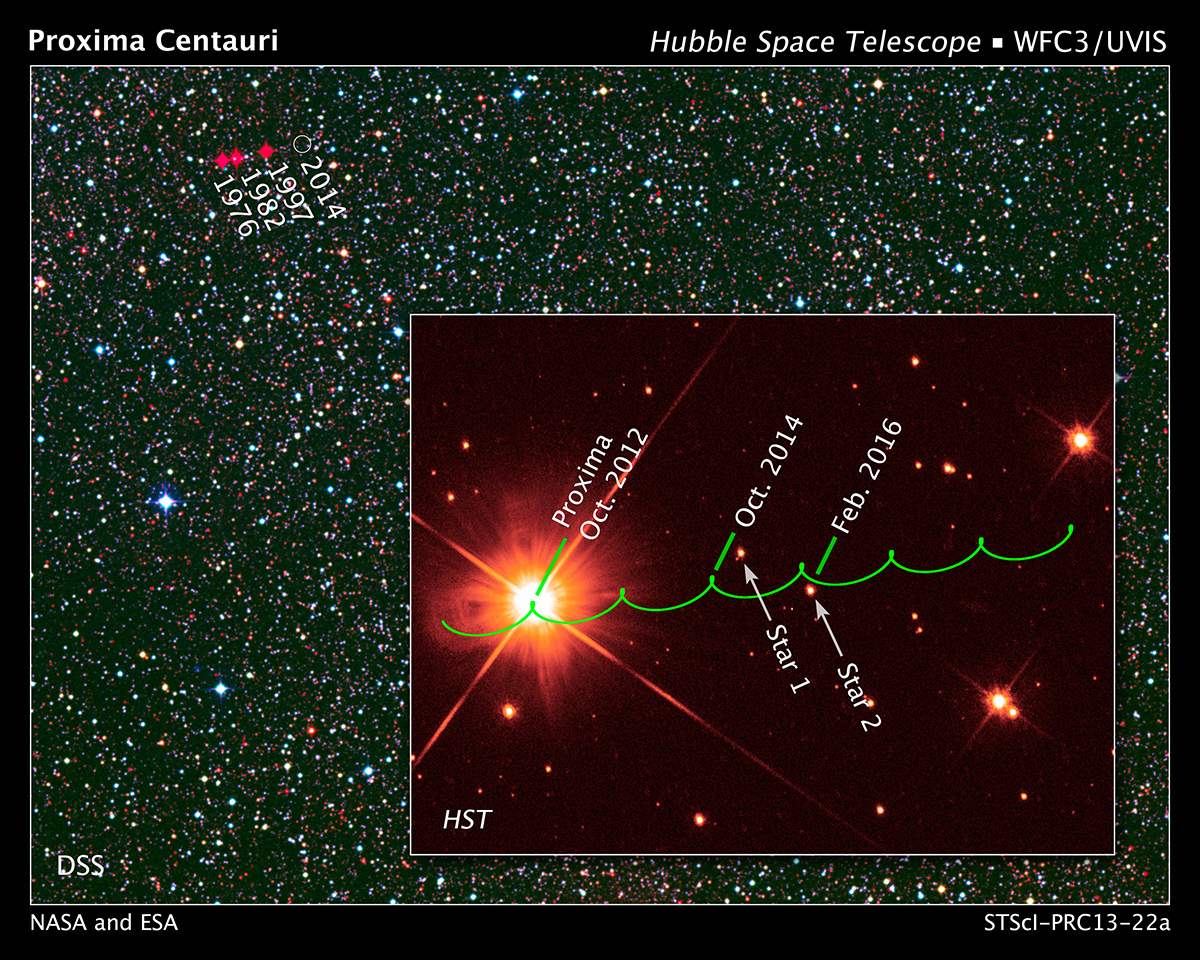

The nearest star to our Sun, the red dwarf Proxima Centauri, is on a course for a rare conjunction with two distant background stars. This alignment will offer astronomers a unique opportunity to look for planets orbiting close to Proxima Centauri. In addition, astronomers will be able to precisely measure the mass of this isolated red dwarf. Observations from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope were used to plot the star's trajectory across the sky with enough precision that astronomers can predict two "close encounters" of the stellar kind with Proxima Centauri. The red dwarf passes nearly in front of a 20th-magnitude background star in October 2014 and a 19.5-magnitude star in February 2016. The warping of space by Proxima Centauri's gravitational field will cause the image of each star to be very slightly offset from their real positions on the sky. The amount of offset can be used to measure Proxima Centauri's mass — the greater the offset, the greater the mass of Proxima. If Proxima Centauri has a planet, it may produce a small second position shift due to the companion planet's gravitational field. The stars will shift very slightly in their apparent position, an estimated 0.5 milliarcsecond and 1.5 milliarcseconds, respectively. (A milliarcsecond is the angular width of a nickel in Honolulu, Hawaii, as viewed from the distance of New York City.) Hubble can make measurements as small as 0.2 milliarcsecond. The European Space Agency's Gaia space telescope and the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope on Mt. Cerro Paranal in Chile may be able to make comparable measurements. These so-called microlensing events will last from a few hours to a few days. Because Proxima Centauri is so close to Earth, the area of sky warped by its gravitation field is larger than for more-distant stars, and this makes the observations easier to look for shifts in apparent stellar position caused by this effect. So far all attempts to detect planets around Proxima Centauri have been unsuccessful. Radial velocity and astrometric observations, which can measure the gravitational wobble of a star due to the pull of an unseen companion, have not detected the presence of planets. Astrometric observations rule out giant planets with anything larger than 80 percent of Jupiter's mass with a period of less than 1,000 days. Likewise radial velocity observations exclude the presence of any planet the mass of Neptune or larger within an orbital radius equal to Earth's orbit (assuming the orbit is not face-on to Earth or similarly inclined at a steep angle). Nor have planets been found transiting across the face of the star, which would happen if the planet's orbit were edge-on to Earth. But now, by looking for microlensing effects during these rare stellar alignments, smaller terrestrial planets around Proxima Centauri could be detected. A team lead by Kailash Sahu of the Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Md. first searched 5,000 stars in the Luyten Half-Second catalogue of stars that have a high rate of angular motion across the sky for possible alignment events. "Proxima Centauri's trajectory turned out to offer one of the most interesting opportunities because of its extremely close passage to the two stars," says Sahu. Because it is so close to Earth, Proxima Centauri also moves across the sky at a comparably high angular rate. It crosses a piece of sky with the apparent width of the full Moon every 500 years. Red dwarfs are the most common class of stars in our Milky Way galaxy — any such star that has ever been born is still shining today, because they live longer than the age of the universe. Therefore, getting a precise determination of mass is critical to understanding a star's temperature, diameter, intrinsic brightness, and longevity. For every star like our Sun, there are approximately 10 red dwarfs in space. Because lower-mass stars tend to have smaller planets, red dwarfs are ideal places to go hunting for Earth-sized planets. At a distance of 4.2 light-years from Earth, Proxima Centauri is just 0.2 light-years from the more-distant binary star Alpha Centauri A+B. These three stars are considered part of the triple-star system, though Proxima Centauri evolved in isolation from the two Sun-like companion stars. This paper has been submitted to the Astrophysical Journal and Dr. Sahu is presenting these results at the meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Indianapolis, Indiana. CONTACT Ray Villard Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Md. 410-338-4514 villard@stsci.edu

Picture Credit: NASA and ESA

Text from Hubble Space Telescope Site Shining brightly in this Hubble Space Telescope image is our closest stellar neighbor: Proxima Centauri. Proxima Centauri lies in the constellation of Centaurus (the Centaur), just over four light years from Earth. Although it looks bright through the eye of Hubble, as you might expect from the nearest star to the solar system, Proxima Centauri is not visible to the naked eye. Its average luminosity is very low, and it is quite small compared to other stars, at only about an eighth of the mass of our Sun. However, on occasion, its brightness increases. Proxima is what is known as a "flare star," meaning that convection processes within the star's body make it prone to random and dramatic changes in brightness. The convection processes not only trigger brilliant bursts of starlight but, combined with other factors, mean that Proxima Centauri is in for a very long life. Astronomers predict that this star will remain middle-aged — or a "main sequence" star in astronomical terms — for another four trillion years, some 300 times the age of the current universe. These observations were taken using Hubble's Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2). Proxima Centauri is actually part of a triple star system — its two companions, Alpha Centauri A and B, lie out of frame. Although by cosmic standards it is a close neighbor, Proxima Centauri remains a point-like object even using Hubble's eagle-eyed vision, hinting at the vast scale of the universe around us.